The anatomy of a honey bee

A masterpiece of nature.

The anatomy of a honey bee is a miracle of nature, with each part having a specific function in the survival and functioning of the colony. The anatomy and physiology of the honey bee.

The exoskeleton: its protection and structure

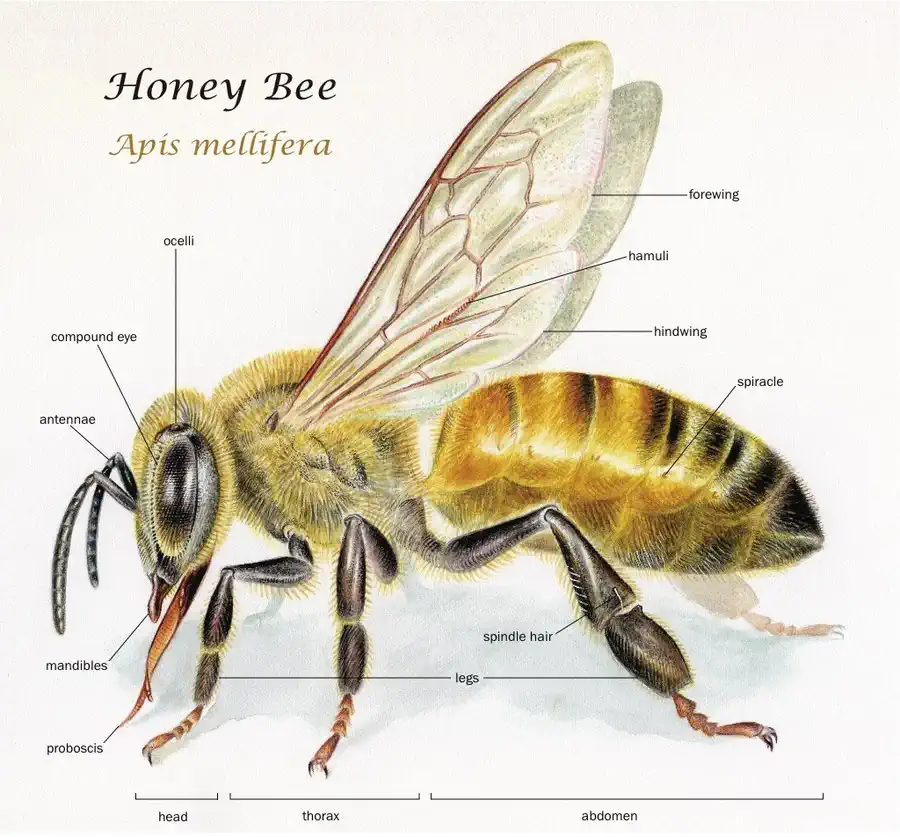

Honey bees, like other insects, have an exoskeleton, a hard outer layer that protects and supports their bodies. This exoskeleton is composed of chitin, a tough and flexible material that provides both protection from enemies and support to the internal organs. The exoskeleton consists of three main sections: the head, the thorax (chest) and the abdomen.

The head: Sensors and food intake

The head of the honey bee has a complex structure that contains several crucial organs:

– Eyes: Honey bees have two compound eyes and three single eyes (ocelli). The compound eyes consist of thousands of tiny lenses, which help the bee detect movement and light, which is essential for navigating and finding flowers. The ocelli help regulate flight and sense light intensity.

– Antenna: The antennae are sensory organs used to perceive scents and pheromones *). They play a key role in communication between bees and help them find food sources.

*) A pheromone is a volatile molecule that transmits messages between individual organisms of the same species.

– Mouthpieces: The honey bee has several mouthparts, including a tongue (proboscis) capable of sucking nectar from flowers. The jaws (mandibles) are used for manipulating objects, such as beeswax and pollen.

The thorax: Location of the wings and legs

The thorax is the middle part of the bee and houses the muscles that control the wings and legs. A honey bee has six legs, each with specific functions. The front legs have special brushes to keep the antennae clean, while the rear legs have a ‘hive’, a special hair field in which pollen is collected and transported to the hive.

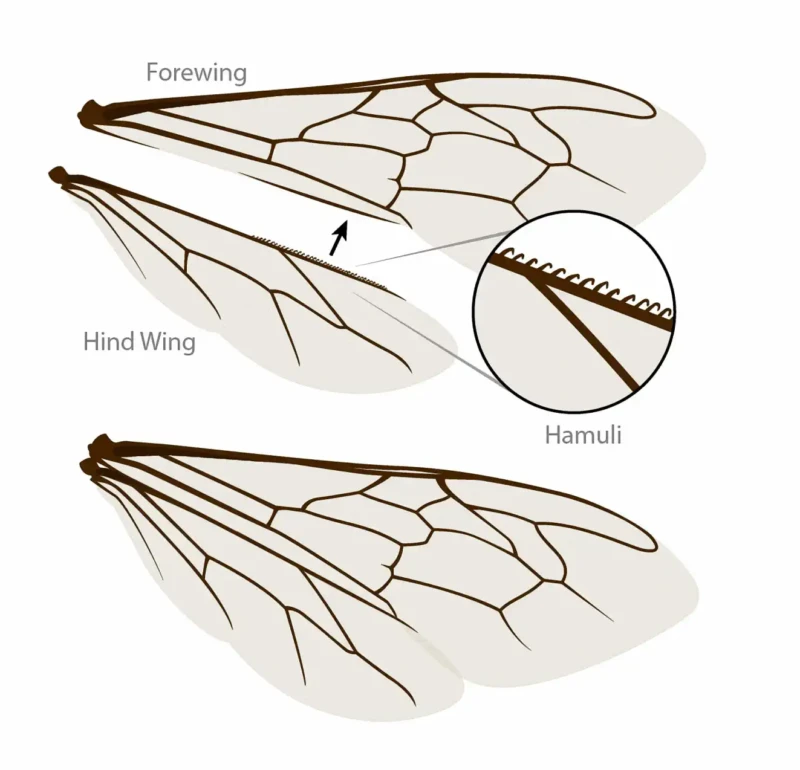

The wings of a honey bee are remarkably efficient. They have two pairs of wings (forewings and hindwings) connected by a series of small hooks, making for powerful and coordinated flight. Bees can move their wings up to 15 times per second, enabling them to travel long distances in search of food.

The abdomen: Reproduction, digestion and defence

The abdomen is the last section of the bee and contains the main organs for reproduction, digestion and defence.

– Digestive system: The digestive system of a honey bee starts at the mouth and runs through the oesophagus to the honey stomach, where nectar is stored. This is later converted into honey. Behind the honey gizzard is the actual stomach, where food is digested and nutrients are absorbed.

– Venom gland and sting: The sting of the honey bee is connected to a venom gland. When a bee feels threatened, it can sting, leaving the sting stuck in the skin and injecting venom. This is an effective defence against predators, but usually results in the bee’s death as the sting is torn away from the body because the sting has a barb.

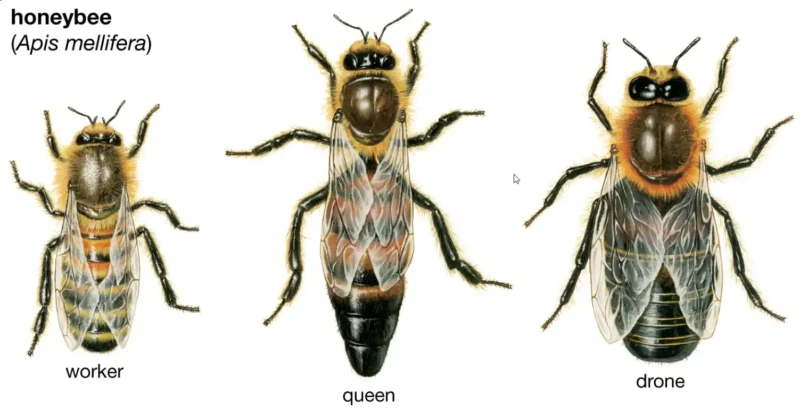

– Reproductive system: In worker bees, the reproductive organs are rudimentary, but in the queen they are fully developed. The queen has spermatheca, a sac in which sperm is stored after mating. This sperm can be stored for years and used to fertilise thousands of eggs.

The anatomy of a honey bee to serve the colony

Each honey bee is designed to fulfil a specific role within the colony. Most bees in a hive are workers, responsible for tasks such as collecting nectar, caring for larvae and guarding the hive. Darren, male bees, have a single purpose: to mate with a queen. The queen herself is the mother of all bees in the colony and is responsible for laying eggs.

Summary

The anatomy of a honey bee is a perfectly tuned mechanism that allows them to survive and thrive in a complex social structure. Each part of their body has a specific function that contributes to the success of the colony. It is this combination of anatomical precision and social organisation that makes the honey bee one of the most successful insect species. Their role in nature, and especially in the pollination of crops, underlines the importance of these small, but extremely important, insects.